How to Price Artwork: the Subjective Price

Basic business pricing strategies—like calculating costs or determining your billable rate—make pricing artwork more approachable. However, it’s the subjective and perceived value of artwork that makes pricing artwork slippery. Still, there are still concrete methods to help determine how to price artwork despite the “relativity” or “subjectivity” of prices in the art market.

The following guides the research involved in selling a client’s art. After determining the minimum price any artwork needs to pay the bills, these questions help weigh and measure a piece’s price against its audience and market.

What can your audience offer?

Collectors, enthusiasts, company art initiatives—all have objective guidelines for their purchasing decisions:

- Wealth or budget: what proportion of your income are you willing to spend on a discretionary purchase? Your audience has a budget too. A beginner collector who buys 1-2 pieces a year probably isn’t willing to spend more than 5-10% of their annual income on these purchases.

- Awareness of costs to produce: one advantage of corporate clients (companies or businesspersons) is that they better understand how the cost of time adds up quickly.

- Functional needs: does your piece do something that comparable products could do? For example: shade a room, fill a gap in wall space, custom match a design/brand element, show love to a partner. Your audience will know your art has more value than a purchase from a big box store, but they’ll still compare your price to it. The price increase needs to be proportional to the value added by the uniqueness of a custom artwork.

- Market price: your audience follows and multiple artists the same way you do. Your vision is uniquely yours, but your pricing will still be compared to the other “competitors” your audience follows.

It’s easy to get wrapped up in how artwork transcends value. (Because it does!) But ultimately, these concrete factors play a major role in your audience’s ability to invest in you.

After considering these factors, the subjective comes into focus:

- Desire: do they want your work and how much? How much more than alternative (cheaper) solutions?

- Affect: does the work make them feel something that nothing else can?

A potential buyer should acknowledge the immeasurable worth of your work—but how much more can they realistically afford? Evaluating the financial situation of our audience members (or simply asking them) provides concrete guidelines for how to price artwork.

What part of the audience’s offer can the producer influence? And how?

You can’t make your audience wealthier so they can afford your work. But other factors above can be influenced:

- Educate about production costs: even if they expected big box store prices on art, when an audience member really values your work, it’s a good chance to educate your audience about the cost and time required to produce something they appreciate.

- Educate about process and materials: do they know about the rigor of your practice? The exclusivity of your technique? What about the quality of your materials? These are all major selling points which get glossed over by focusing on subjective responses to the “image” (or form) itself.

- Distinction from the competition: That competition may be a set of blinds from a big box store or another artist. Regardless, it instills trust in your pricing when it’s clear you’ve researched their alternatives.

It’s not just desire and affect. Don’t expect to inspire all potential buyers to simply want the work more or fall more in love with it to justify prices. By starting with concrete factors, subjective wants or needs give helpful context to the sales process. Therefore, desire and affect don’t need to drive the whole sale. Instead, they help account for marginal differences or justify differences in perceived value.

But can a producer heighten an audience’s desire? (And offer?)

YES. This is the end goal of marketing and sales in art—help the audience see an artwork’s true value, thereby justifying the price. There are a lot of marketing and sales strategies. A simple one we like is Billy Broas’ Five Lightbulbs—identify the audience’s status quo, and give them a vision of how our offer gets them out.

The concrete market research tactics here are a first step in identifying an audience’s status quo and account for it when determining how to price artwork. If you have artwork you’re ready to sell, you need support. Coaching or management are both ways we can help you develop your marketing and sales strategy.

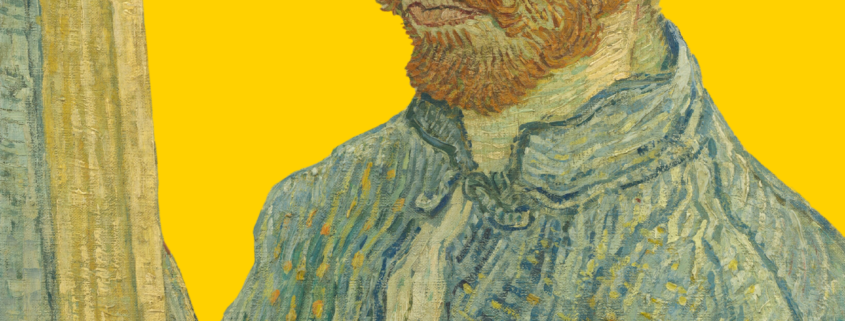

Banner art credits: Portrait of Vincent van Gogh, 1925/1928 by an anonymous imitator. It’s unclear whether this piece was a respectable, uncanny study of Van Gogh’s work or a forgery trying to profit posthumously on the artist’s distinctive style.